Basics, Cargo Terminals, CARE, Ground Handlers, Regulators

All about the Weight and Balance Manual

During a presentation on ULD at the 2016 IATA Ground Handling Conference the audience was asked to indicate whether they were aware of the existence of a document known as the Weight and Balance Manual (WBM). About 10% of the audience raised their hands, this number fell by half when they were asked if they had actually had the opportunity to read a WBM and fell further again to just a handful when asked if they had actually studied the references to ULD contained in the WBM. Should this be a surprise? Not really, as there are more than a few structural obstacles that stand between the people providing ground handling and cargo services and the airlines who have the responsibility for flight safety.

What is the Weight and Balance Manual?

The weight and balance manual is part of the aircraft operating documentation. No different to flight operations manuals and maintenance manuals, the WBM provides detailed and specific instructions to the operator of the aircraft on how it must be loaded in order to be safe. Some might consider that the only important aspect of the WBM is to ensure that the aircraft’s center of gravity is within limits, but this would be incorrect. The WBM is much much more. It even contains instructions on how the contents of the cargo holds are to be secured and restrained and it is in this area that the references to ULD appear.

How does the WBM apply to ULD?

The WBM provides specific requirements for any ULD that may be positioned in the aircraft with references to base dimensions and contours as well of course as maximum weight. It also covers variables such as maximum permissible running load and area load and, when it comes to ULD, it specifies what performance and/or certification standards are required from the ULD. Indeed the WBM is the document that defines what the aircraft “expects” when it is being loaded and the important thing to understand here is that the aircraft shall not be presented with any “surprise” loads or conditions during flight because if such events occur they can result in unexpected and potentially catastrophic consequences.

The WBM provides specific requirements for any ULD that may be positioned in the aircraft with references to base dimensions and contours as well of course as maximum weight. It also covers variables such as maximum permissible running load and area load and, when it comes to ULD, it specifies what performance and/or certification standards are required from the ULD. Indeed the WBM is the document that defines what the aircraft “expects” when it is being loaded and the important thing to understand here is that the aircraft shall not be presented with any “surprise” loads or conditions during flight because if such events occur they can result in unexpected and potentially catastrophic consequences.

How does all this work in daily operations?

There are two major challenges facing the industry when it comes to ensuring WBM compliance each and every flight:

- Each aircraft’s WBM is a proprietary document with circulation restricted to the operator of the respective aircraft. This means that the airline is not permitted to simply make copies of the WBM and circulate to the various parties who play a part in the loading process.

- To a very great extent airlines have outsourced the majority of their ground handling and cargo loading operations to third-party service providers who have no direct relationship or access to the contents of the WBM and indeed probably have very little understanding of the relevance of the WBM to the particular operations they carry out for their customer airlines.

This situation creates a “knowledge vacuum” in a safety critical area of aircraft operation, and there is plenty of both anecdotal and statistical evidence that this results in a poor quality of aircraft loading safety. So what can the industry do about this state of affairs? The good news here is that the IATA ULD Regulations, while not replacing in any way or form the WBM, acts as a facilitator.

Section 1.4.2 of the ULDR contains 18 Specific Responsibilities applicable to the ULD operations of any airline, each of these responsibilities will deliver directly or indirectly compliance with the WBM and any airline who is delivering on all of these 18 Specific Responsibilities can feel comfortable that their ULD operations will not be in contradiction to the requirements of the WBM.

Section 1.4.3 of the ULDR addresses the delegation of responsibilities by airlines to third parties, Sec. 1.4 the requirements for “Operators Instructions” while Sec.1.5 covers “Other Parties Responsibilities” and this is where it is particularly important that the transmission by the airline and receipt and understanding by the service provider of WBM related requirements is carried out in an accurate and reliable manner so that nothing falls between the cracks.

Easy enough? Perhaps on the surface yes but when it comes to ULD the devil lies in the details, as different airlines with different ULD are handled by multiple different parties in different locations at all hours of the day and night creating a “black hole” of differing requirements expected of the service providers.

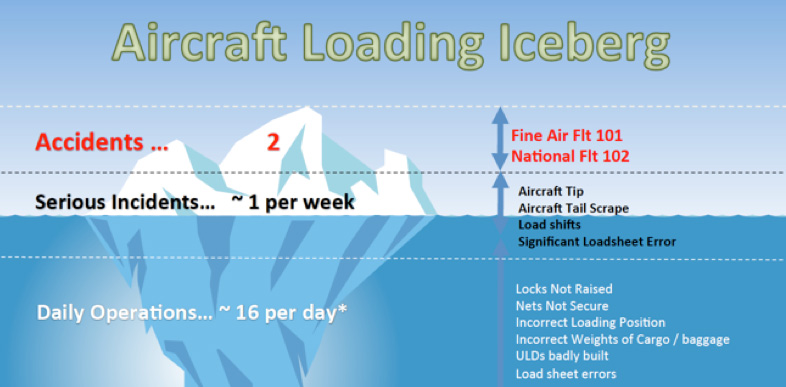

Part of the ULD presentation made at IGHC comprised data extracted from the IATA STEADES database, which collects safety related data from airline and consolidates into an industry level picture and from the IATA GDDB – Ground Damage Database.

Both sets of data point to unacceptably high level of incidents all of which have their basis in a lack of attention to the requirements of the WBM. Had the job been done in accordance with the WBM these incidents would not have happened. Acceptable? No…and unfortunately there is a deep-seated lack of awareness that a built-up ULD must be in compliance with the WBM when it reaches the aircraft, generally a point at which it is very difficult to do anything without a significant commercial knock-on effect and the result is all too often ULD end up on-board the aircraft in a condition that does not meet the requirements of the WBM.

However difficult this task may be, the industry simply cannot afford to neglect this safety critical component of cargo loading, and until the day arrives that each and every ULD being loaded to an aircraft is 100% compliant with the requirement of that aircraft’s WBM, efforts must continue to improve matters through training, awareness, better facilities, and management focus on ULD safety.